The Marine Discovery Centre's Henley Beach 3D Beachcombing Experience officially launches today, offering an exciting new way to explore the coastline from anywhere in the world. This interactive virtual tour covers approximately 600 metres of Henley Beach, allowing users to discover and interact with 3D models of objects found during the Centre’s beachcombing excursions. Each item includes detailed educational insights, making it a fantastic learning tool for students, educators, and nature enthusiasts. Designed as an accessible alternative to in-person visits, this resource is especially valuable for classrooms and individuals in regional areas who may not have easy access to the beach.

Funded by Green Adelaide and developed in partnership with ABM visual, this innovative project uses CAPTUR3D’s advanced Matterport technology to create a rich and immersive digital experience. The platform enables interactive features such as custom tags and virtual staging, enhancing the learning experience while maintaining the Centre’s unique educational style. Now available online, the 3D Beachcombing Experience is set to become a valuable resource for marine education, fostering a deeper connection with South Australia’s coastal environment.

Written by Alesha Brewer

We seem to hear about it once or twice a year – strange glowing stuff washing up on some of SA’s best-loved beaches. News teams race out to film kids and adults alike excitedly splashing around in water filled with what looks like the inside of a particularly vivid glowstick. But what exactly is this unusual phenomenon?

Bioluminescent algae graced Port Lincoln in August of 2023 (Nine News SA)

It’s best to first understand how this glowing happens. It’s a result of bioluminescence, a chemical tool that evolved numerous times in marine life that is used in a wide range of applications. That giant, creepy, evil-looking anglerfish in Finding Nemo was probably most people’s first introduction to this concept – here we see bioluminescence used as a hunting tactic to lure in unsuspecting prey.

While a great educational moment, I have to question the necessity of making children (and adults) terrified of what might be hiding in the ocean (Walt Disney Studios)

Heaps of other open ocean animals can glow too, to signal to members of the same species, scare off potential threats, or create distractions to throw predators off their trail. Many species, such as the lanternfish, can create specialised chemical compounds that react and glow (just like the inside of a glowstick!). Other species, however, need to rely on a symbiotic relationship with special glowing bacteria.

A firefly squid in the Sea of Japan using bioluminescence to camouflage with light from the surface (National Geographic)

It's the enzyme called luciferase that is responsible for catalysing the reaction of glowing chemical compounds and ultimately creating some strikingly glowing bacteria. There are a number of bacterial groups that can glow, some of which are free-floating throughout the world’s oceans, and many of which form symbiotic relationships with larger organisms. Usually, the bacteria provide the larger species with the ability to glow, and in return, the bacteria have a safe environment to live in and a reliable source of energy.

But it’s not just bacteria that glows. In fact, what we see washed up on our beaches is usually bioluminescent algae. Unlike bacteria, true algae belong to the domain eukaryota, meaning their cells contain a nucleus (amongst other differences). The underlying mechanisms of their bioluminescence are largely the same, however, in algae, it’s almost exclusively used as a defence mechanism.

The tiny, individual cells of algae glow when there is a disturbance in their environment, such as the movement of the waves or of other, larger creatures. That’s why it becomes more visible along the shoreline, where the tide is constantly pushing it up against the sand. It’s also why people kicking and splashing in the water create impressive, glowing splashes.

An abundance of bioluminescent algae washed up on a beach in the Maldives in 2010 (Doug Perrine, Nature Picture Library)

However, the reason why we see such large and concentrated amounts of bioluminescence every now and then is the result of large algal blooms. When the conditions are just right, algae can rapidly multiply and dominate their environment, taking advantage of plentiful energy from waste in the water or stagnant currents. Bioluminescence in this case is believed to be a tool to ward off grazing from predators, but produced alongside this beautiful glow is several kinds of highly toxic compounds. These not only prevent predation but can actively harm marine life, poisoning fish as well as shellfish and important filter feeders. While algae and their defence mechanisms are a natural part of marine ecosystems, in exponentially increasing populations they can cause more harm than good.

That’s why it’s important to note that, despite its beautiful and alluring appearance, it’s best to avoid touching or swimming in glowing waters. Especially important is to keep pets away from the water, lest they drink and ingest harmful toxins. There’s plenty of beautiful photos and videos you can take without being in the water yourself – a well-thrown rock can create some dazzling splashes!

A little creativity in your photography can help keep yourself and others safe (Hasan Jasim)

As a high school student did you know you wanted to go into marine biology?

Georgie: No, I didn’t - throughout high school I did enjoy science, but in Year 12 I also did well in English, History and Indonesian. This led me to begin a Bachelor of Arts/International Studies with the plan that I would try to get into journalism. When I discovered that I did not enjoy this as much at a university level, I transferred to a Bachelor of Science after a year, and then a major in Marine Biology a year later. I have always loved being at the beach and learning about the environment and all things nature, and my brain seemed to work better in the realm of sciences rather than arts.

Jess: Yes, I have always had a huge love and passion for the ocean and ocean animals. It started with the typical large cetaceans (dolphins and whales) that everyone loves, then my interests grew to all other aspects of the ocean. This is everything from plants, marine algae (seaweed) and all other animals big or small!

Did you have to do any volunteer work or extracurricular activities? How did you begin to start your career in marine biology?

Georgie: I actually got my current job at the Marine Discovery Centre through volunteering here. After I finished my university studies I wanted to gain more local knowledge of our marine environment, and began volunteering at the centre once a week, helping out with school excursions as well as aquarium maintenance and fish feeding. I volunteered for 2.5 years, and when a position became available, I was offered a paid role here as a resident marine scientist. Throughout the years I have also volunteered with the Adelaide Dolphin Sanctuary Action Group, participated in some dune plantings and restoration, and also completed some workshops and courses including Coastal Ambassadors and Climate Ready Communities. I found all of these experiences to be helpful to compliment my formal education and learn how people and communities can make a difference to help our marine environment.

Jess: Volunteer work was not compulsory within any of my marine studies, although I did complete some small volunteering work with beach clean-up groups and then underwent an internship at the Marine Discovery Centre, where I continued to volunteer once my internship was completed. These experiences were the most beneficial activities I undertook throughout my degree as they provided me with a wealth of extra knowledge as well as providing me experience in the workplace with hands on activities.

What did you do during university when studying marine science?

Georgie: I completed a Bachelor of Science (Marine Biology) at the University of Adelaide, with an additional Honours project. I liked how the course began with the basics of biology and environmental sciences, with courses in Zoology, Botany, Ecology and Geology. The third year then took what we had learnt and applied it to Marine Sciences. There were various field days and camps which were really great opportunities to see and experience some of these ecological concepts in nature. My honours project also involved a lot of field work taking part in surveys of juvenile fish populations in a variety of coastal habitats around South Australia such as mangrove creeks, mudflats, seagrass meadows and saltmarshes. Throughout my third year and during Honours we did a lot of project creation, experiment proposals and utilising statistics to support our findings. I was also able to gain some extra experience by volunteering my time in laboratory work for PhD students, usually some microscope work and identification of marine invertebrates.

Jess: During university there was some practical experiences out in the field as well as in the lab which I found beneficial to apply my knowledge of marine science.

I also had a part time job in retail while I completed my studies, proving the importance of time management and planning my workload ahead.

Was it hard to find a job in field or with your degree?

Georgie: After completing my studies, I did find that there wasn’t a lot of work advertised that I felt I could apply for. A lot of the roles advertised were senior roles or for people with more experience in the workplace. It was for this reason that I started looking for volunteering opportunities, to try and gain some more practical experience. I was lucky then to gain a paid position after 2.5 years. Other volunteers at the centre have gone on to gain employment in aquariums or eco-tourism in WA and Queensland. It can also be helpful to form connections with a network of people working or volunteering in environmental sciences where you live, to start to get your name out there and build a foundation of contacts you can call on for advice, work experience or job opportunities.

Jess: I was very fortunate to be successful in my application for the Marine Discovery Centre as the first marine science job I applied for. Although in this field I believe it is all about networking and having experience, subsequently having volunteer and internship experience is very beneficial!

What advice would you give someone who wants to pursue marine biology?

Georgie: I would tell them to follow their passions – if you have an interest in a particular animal, habitat, or other area, then it can be helpful to hone your expertise. If your university offers an internship program as a part of your studies, then try and take part in these. Try and get out in nature, either the beach, coastal habitats or underwater, and just observe what you see. Take the time to stop and watch or listen to see what is happening in the environment around you, and how this might play a role in the larger ecosystem. By being curious and inquisitive, we can learn so much from the world around us. You can also take other passions and interests and try to integrate these with marine biology – not everyone who studies marine biology will go on to be a “marine scientist” working in the ocean or a lab. You could work in education, community engagement, citizen science groups, tourism or art and still incorporate marine biology into these fields.

Jess: I would say if Marine Biology is something you are passionate about, then absolutely go for it, because it is this passion that will get you places in your future. Take any and every opportunity that comes your way, whether it may be practical experience within your degree, information days, volunteering opportunities, or internships. The best thing you can do is to get your name out into the community, by completing some the previously stated opportunities, this will help put you one step above everyone else.

What would you have done differently to help you with marine biology?

Georgie: There are things I would have liked to have done if the financial barriers weren’t there, such as travelling to more places around South Australia and Australia to explore and experience more marine and coastal environments. I am still on a journey with Marine Biology, as this is my first job in the field, and would like to explore opportunities for different pathways other than environmental education in the future.

Jess: If I could do my degree again, I would have tried to gain more experience in different fields within marine biology, gaining experience with many different companies, organisations to help further my knowledge whilst studying.

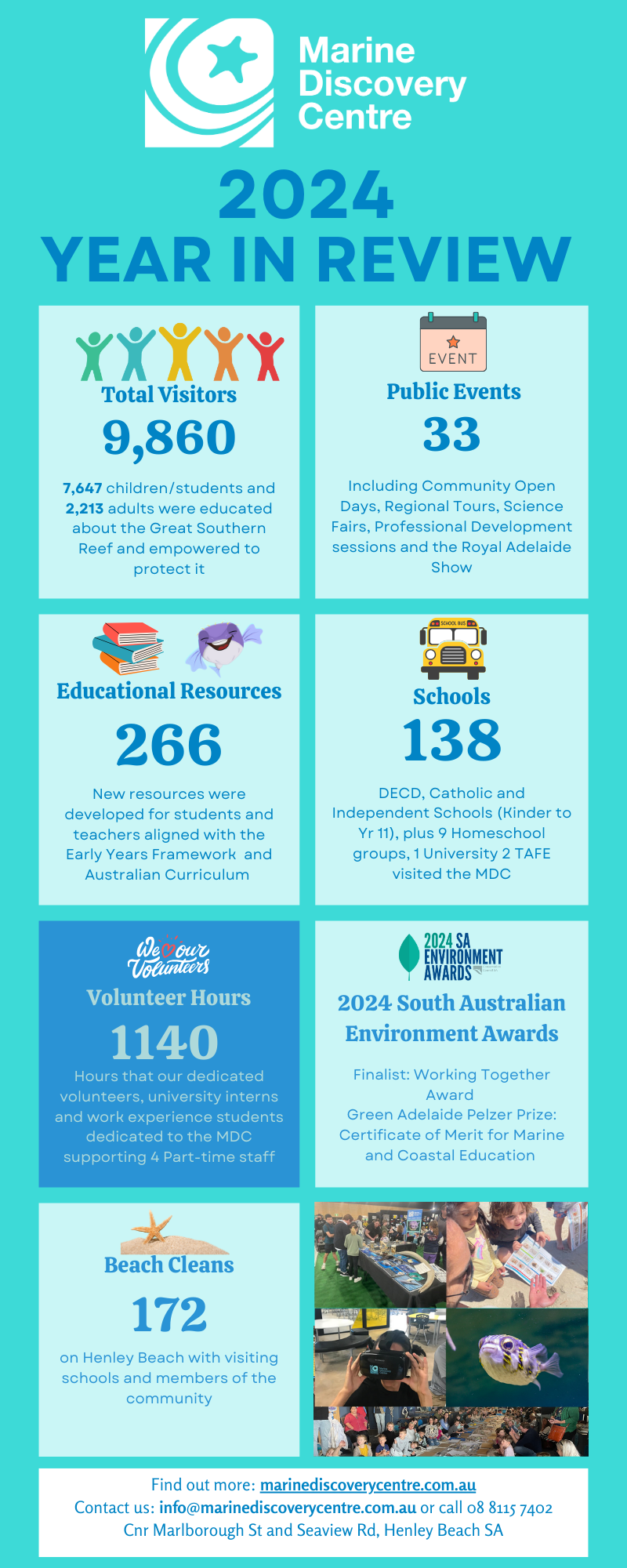

On World Environment Day, Wednesday 5 June, the Marine Discovery Centre was acknowledged at the 2024 South Australian Environment Awards.

Marine Discovery Centre team pictured: Georgie Kenning (Marine Scientist), Jess Leopold (Marine Scientist), Carmen Bishop (Director), Karno Martin (Cultural Educator)

The Marine Discovery Centre was a finalist in the 'Working Together Award'

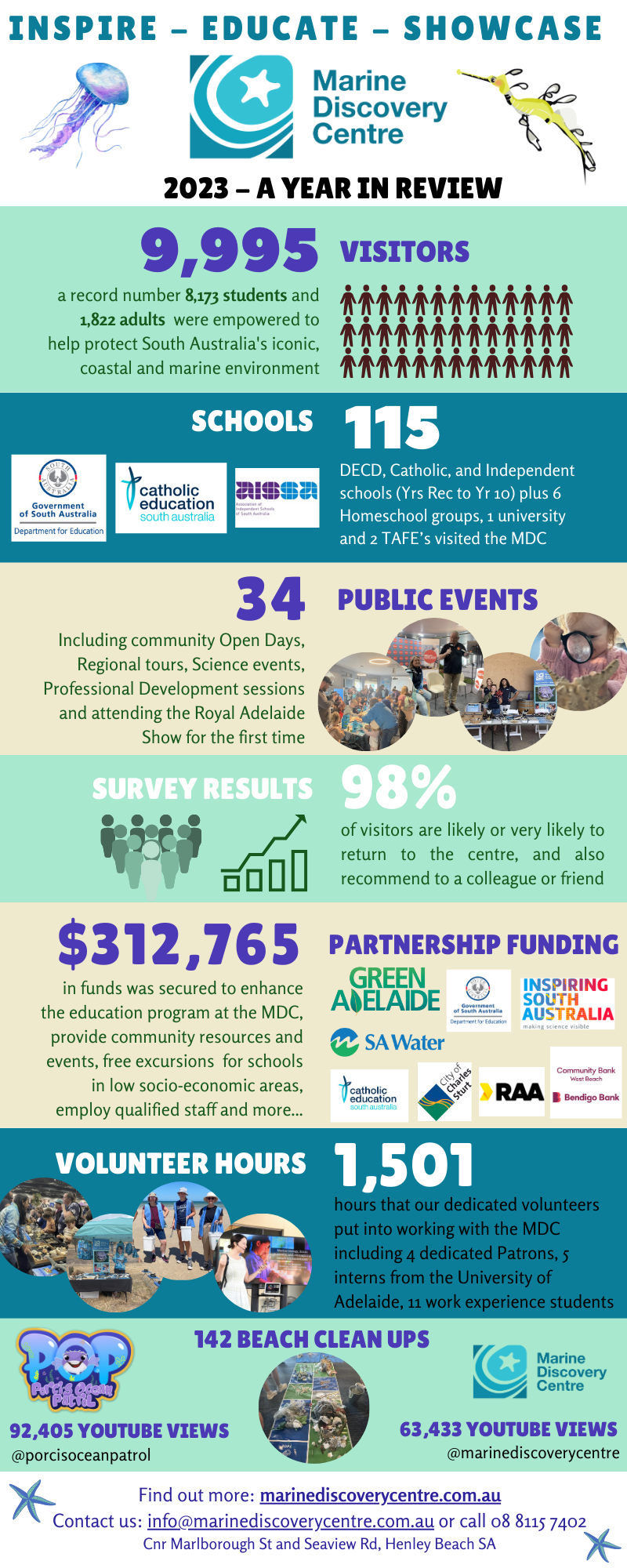

Established in 1997, the Marine Discovery Centre has emerged as a beacon of marine science education in South Australia.

Today, with an annual visitation of 10,000 individuals through school and community visits, the Centre fosters environmental consciousness and cultural appreciation in South Australians.

Through engaging marine exhibits and workshops highlighting Indigenous knowledge, the Centre encourages scientific curiosity and instils a profound respect for the ancient wisdom of Australia's First Peoples in managing marine ecosystems.

In addition to a Certificate of Commendation for the Green Adelaide Pelzer Prize.

Carmen Bishop: Certificate of Merit for Marine and Coastal Education

We congratulate all of the winners and finalists who are making a difference - 2024 SA Environment Awards

Aliens in Our Oceans

Imagine encountering an otherworldly creature, seemingly from a distant galaxy, right here on Earth. This scenario may not be as far-fetched as it sounds when we consider the incredible cephalopods—cephalopods, such as octopuses and cuttlefish, possess truly unique and fascinating features that often seem straight out of science fiction.

Masters of Disguise

One of the most mesmerizing abilities of cephalopods is their unmatched talent for changing colours and patterns. Octopuses and cuttlefish can rapidly alter their skin texture and colour, enabling them to blend seamlessly into their surroundings or dazzle with vibrant displays. This remarkable camouflage not only aids in evading predators but also in hunting unsuspecting prey.

Cuttlefish, known for their hypnotic beauty, have been observed using their colour-changing abilities in surprising ways. Some species employ hypnotic colour displays to entrance their prey, momentarily freezing them in place before launching an attack—a tactic that seems straight out of a science fiction thriller. These colour changing abilities are not only used for hunting and camouflage but also communication and even tricking potential mates and rivals.

Alien Bodies

Cephalopods possess a unique copper-based blood pigment called hemocyanin, as a result, their blood is blue. This adaptation allows their blood to transport oxygen efficiently in the cold, oxygen-scarce depths of the ocean. Furthermore, their soft bodies lack the rigid internal skeleton typical of most animals, giving them exceptional flexibility and allowing them to squeeze into tight spaces.

Incredible Intelligence

Cephalopods are renowned for their astonishing intelligence, especially considering they lack a backbone. Octopuses, in particular, have demonstrated problem-solving skills, sophisticated hunting strategies, and even the ability to learn by observation—traits traditionally associated with higher vertebrates.

What's more, cephalopods possess a distributed nervous system, with a significant portion of their neurons located in their arms rather than centralized in their brains. This decentralized setup contributes to their incredible dexterity and allows their arms to exhibit complex behaviours even when severed from the body.

Multiple Hearts:

Adding to their uniqueness, cephalopods have three hearts—one systematic heart that pumps blood around the body and two branchial hearts that pump blood to the gills. This arrangement supports their high metabolic rates and active lifestyles, ensuring that oxygen reaches all parts of their bodies efficiently.

Global Distribution:

Cephalopods inhabit diverse marine environments worldwide, from shallow coastal waters to the deepest ocean trenches. They exhibit remarkable adaptability to different ecosystems and have even managed to thrive in regions affected by human activities, making them intriguing subjects of study for marine biologists.

In summary, cephalopods, especially octopuses and cuttlefish, truly embody the concept of "aliens in our oceans" with their extraordinary features and behaviours. Their ability to change colour and texture, coupled with their intelligence, adaptability, and otherworldly anatomy, make them some of the most fascinating and enigmatic creatures on our planet. Studying these marine marvels not only sheds light on the incredible diversity of life in our oceans but also challenges our understanding of what it means to be intelligent and adaptable in the vastness of the underwater world.

Footage of a cuttlefish hypnotising a crab

By Isaac Duke

Article written by Florbela Morgado

The Marine Discovery Centre, located at Henley Beach SA, provides marine and coastal learning experiences and activities, by direct contact, encouraging children and adults to discover and appreciate the marine life and the importance of its conservation and protection.

The centre is divided in four areas, meticulously prepared to captivate the visitors’ attention and curiosity. Visitors in each area are guided by very passionate educators turning it into a unique experience of direct contact with marine and freshwater live animals, Aboriginal culture, biodiversity and ecosystems.

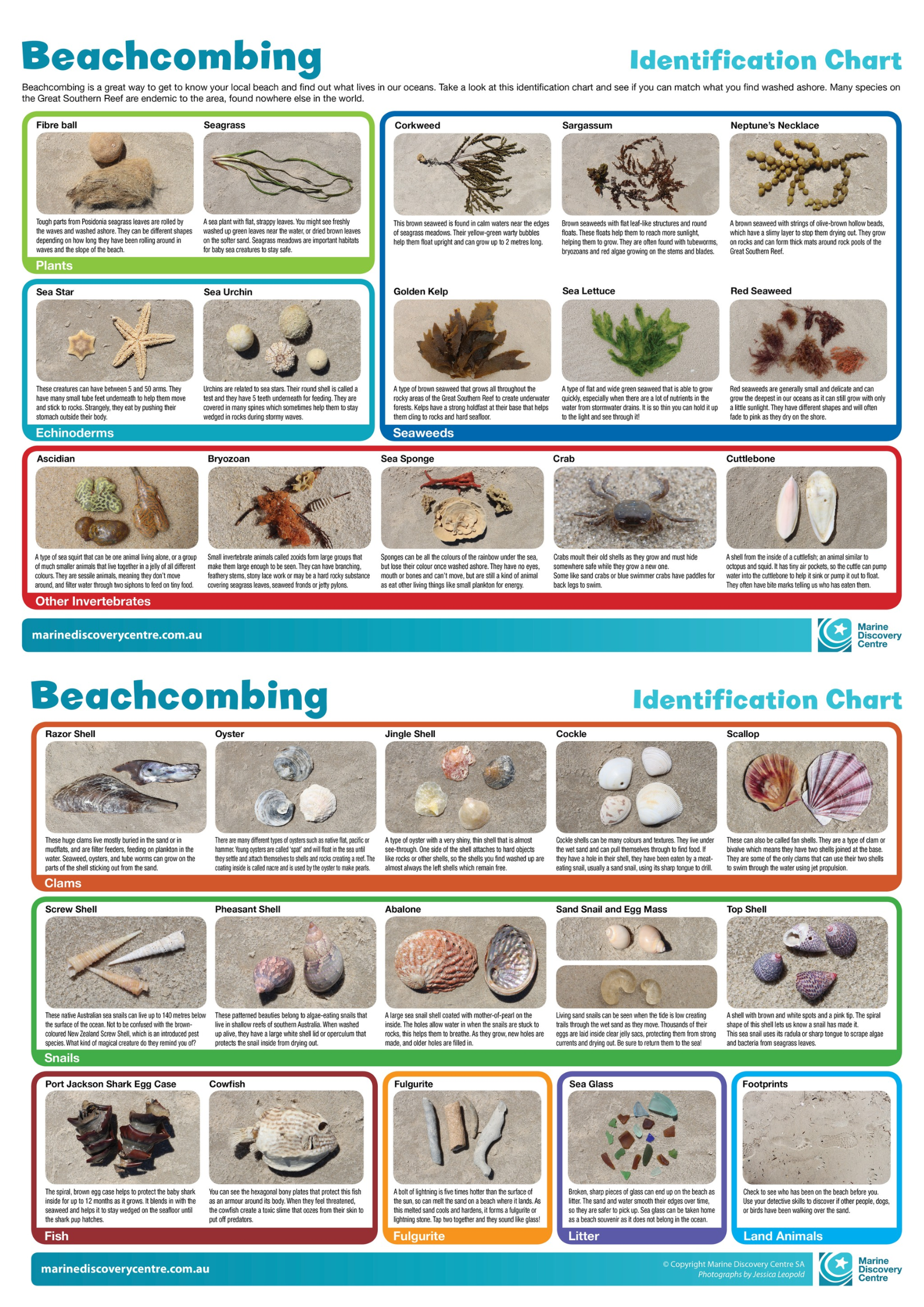

Beach exploring experience

Conveniently located close to the beach, visitors experience a guided walking tour through the Henley Beach sandy coast, giving children and adults, the opportunity to explore the diversity of fauna and flora, brought to the shore by the tides, such as shells, sea stars, seaweed, sea snails and many other interesting things, with informative scientific guidance.

Figure 1: Images from the beach walking tours,a) Sea star commonly known as “feather star” found on the sand during low tide; b) Sea snails, Jujubinus polychroma sp., found in small pools during the low tide; c) Sand sculpture of a seahorse made by the children. (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

Figure 1: Images from the beach walking tours,a) Sea star commonly known as “feather star” found on the sand during low tide; b) Sea snails, Jujubinus polychroma sp., found in small pools during the low tide; c) Sand sculpture of a seahorse made by the children. (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

The Centre

When entering the Marine Discovery Centre, we immediately feel transported into an underwater environment as soon as we walk through the doors, with two large Salmon Catfish, (Neoarius leptaspis sp), welcoming and inspiring curiosity among children and adults, about the diversity of marine ecosystems and about other sea wonders they are about to experience in the Centre.

Figure 2: Two Salmon Catfish, Neoarius leptaspis sp., welcoming visitors at the front door entry of the Marine Discovery Centre. (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

Figure 2: Two Salmon Catfish, Neoarius leptaspis sp., welcoming visitors at the front door entry of the Marine Discovery Centre. (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

Inside the Marine Discovery Centre, visitors experience interactive exhibitions designed for educating and inspiring conservation, to protect our river systems, to protect the marine environment, and awareness about water conservation.

Live Fish Tanks

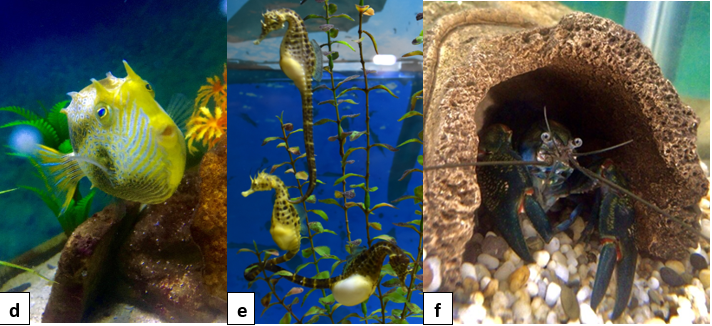

The captivating beauty of live fish tanks displaying both, marine and freshwater environments, give visitors a close view of the underwater diverse ecosystems.

These carefully maintained water tanks offer visitors the opportunity to discover the wonders of live aquatic species such as Seahorses, different species of Pufferfish, Ornate Cowfish, Murray River Turtle, native Oysters, Sea Stars and many other local and non-local species. Some of the smallest babies of the sea, the delicate baby seahorses and sea star babies, that can be seen in the water tanks were born in the Marine Discovery Centre.

The virtual reality headsets provide to visitors the sensation of being transported to an underwater world, immersed by images, providing a deeper visual and multisensory connection to the real underwater environment. Visitors also have the opportunity to see an exceptional collection of seashells and whale bones, with information about their different species and sizes.

Figure 3: In water tanks, d) Ornate Cowfish Aracana ornate sp.; e) Pot-Bellied Seahorse Hippocampus abdominalis sp.; f) Common Yabby Cherax destructor sp.; (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

Figure 3: In water tanks, d) Ornate Cowfish Aracana ornate sp.; e) Pot-Bellied Seahorse Hippocampus abdominalis sp.; f) Common Yabby Cherax destructor sp.; (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

Aboriginal Culture

A Captivating display of ancient aboriginal tools and instruments, with demonstrations of their appropriate techniques, used in traditional fishing, hunting and music playing allow visitors to experience the Kaurna cultural heritage of this region, and the importance of the “sea country” in the aboriginal culture.

Figure 4: g) and h) Ancient aboriginal tools traditionally used for playing music, fishing and hunting. (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

Figure 4: g) and h) Ancient aboriginal tools traditionally used for playing music, fishing and hunting. (Photos: Florbela Morgado 2024)

In Conclusion, through the exhibitions, presentations, demonstrations and interactive learning activities, the role of the Marine Discovery Centre is becoming increasingly important in educating, inspiring and protecting our marine and freshwater environment. The experience strongly encourages children to interact with the marine environment and its ecosystems.

References

Edgar GJ (2000) ‘Australia Marine Life: the plants and animals of temperate waters.’ (Reed New Holland: Sydney)

Here at the Marine Discovery Centre, we’re lucky to host a number of aquatic animals from our freshwater rivers as well as from the wilds of the Great Southern Reef (like Porci, our favourite little mascot!)

Porci ready for a snack! Image credit: Alesha Brewer

But making sure these guys have a safe and clean environment to live in isn’t as simple as just dumping some water in a tank. Just like how we need the right composition of chemicals in the air to breathe and keep our lungs healthy, aquatic animals need just the right chemicals in the water to thrive. They need the correct pH and the right amount of salinity, but we especially need to keep an extra close eye on three specific chemicals – ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate – which make up the nitrogen cycle.

So what is the Nitrogen Cycle?

Put simply, it’s the way in which organic waste (such as uneaten food, debris from plants, or animal excretions) breaks down into compounds of nitrogen. Different strains of helpful bacteria in our tanks break this waste from one form to another in 3 main steps.

First, waste is broken down into ammonia (NH3). We can’t tell it’s there as it’s colourless, but our little critters can, as ammonia can be toxic in large doses. It can inhibit growth and development as well as cause damage to the central nervous system. This is especially true especially at higher pH levels, where a higher concentration of unionised ammonia is present which is much more easily able to penetrate through membranes and cause damage to living tissue.

Luckily, we’ve got a second strain of bacteria up our sleeve! This time, the ammonia is turned into nitrite (NO2-). Unluckily, nitrite is even more toxic than ammonia. Even small amounts can damage how well aquatic creatures can move oxygen through their blood. In order to keep our animals safe, we’ve got to rely on one last type of bacteria.

In the final step of the nitrogen cycle, the toxic nitrites are turned into nitrates (NO-3). While still not great to have in the tank, nitrates are far less toxic and really only become harmful at very high concentrations. That’s why it’s important for all aquariums to have the right balance of bacteria that can turn waste into nitrates quickly and avoid creating harmful concentrations of ammonia or nitrite.

We can get rid of nitrates by regularly changing the water in our tanks. Replacing just a few buckets a week does the trick and is an important part of our tank maintenance routines. We also make sure to monitor the levels of nitrogen compounds by testing water samples with chemical indicators, which warn us if something is going wrong.

Just a few of the chemical tests we use regularly to keep our tanks healthy. Image Credit: API

While it’s great that we can rely on our helpful bacteria to help us control waste in our tanks, it introduces some aquatic chemistry that all responsible aquarium keepers should be familiar with. If you’ve got your own aquatic animals at home, or if you’re just thinking about setting up your own tanks, it’s important to be familiar with the science of the environment you’re replicating – to keep your new friends happy and healthy!

Article by Alesha Brewer

References

Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh & Marine Water Quality (2000) Ammonia in water and marine water. Available at: https://www.waterquality.gov.au/anz-guidelines/guideline-values/default/water-quality-toxicants/toxicants/ammonia-2000

Camargo, J.A. and Alonso, Á. (2006) ‘Ecological and toxicological effects of inorganic nitrogen pollution in Aquatic Ecosystems: A global assessment’, Environment International, 32(6), pp. 831–849. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2006.05.002.

Randall, D.J. and Tsui, T.K.N. (2002) ‘Ammonia toxicity in fish’, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 45(1–12), pp. 17–23. doi:10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00227-8.

Artcile by Mary Gordon

Is there any better way to spend a hot summers day than floating on your back in the cooling waters of the ocean, being gently rocked by the waves? Enjoying the sea breeze amongst the distant echo of children’s laughter as they play and build sandcastles on the beach. As you breathe in the freshness of the salty ocean air and relax to the soothing rhythm of crashing waves, suddenly a piercing scream jolts you out of your trance, followed by a shout, just one word, “Shark!”

The word sends shivers down your spine and evokes chilling images of a bloodthirsty predator, silently stalking the depths of the ocean. A sleek body with black beady eyes and razor-sharp teeth, able to remain completely undetected until BAM!

It truly makes for the perfect horror story, one that has been told over and over through blockbuster hits such as Jaws, the Shallows, and the ever so awful Sharknado.

But what do you know about these creatures really?

If you had the chance to come face to face with a shark, would you do it?

In reality, sharks are rather shy creatures which play a crucial role in supporting marine ecosystems, and currently, a quarter of shark species are under threat.

The stigma surrounding sharks makes it challenging to promote their conservation, which is now more important than ever.

Sharks are keystone species in marine environments, meaning they have a significant impact on the ecosystem. Sharks exhibit a top-down control over other species in the community through predator-prey interactions.

Okay, to simplify this I’ll give you an example. Sharks eat sea urchins, and urchins feed on kelp forests which provide habitat for many other species. If shark numbers were to decline, the number of urchins would increase, leading to the overgrazing of kelp and reduction of species that rely on kelp for food and habitat. In this chain reaction, sharks play a crucial role in balancing the system which in turn benefits people in terms of supporting the fishing industry and allowing us to enjoy marine environments and the ecosystem services they offer.

Article by Mary Gordon

The 21st century has seen increasing pressure to tackle environmental issues that have been exacerbated by climate change, and the increased resource exploitation and pollution that comes with a growing world population.

Our modern consumer society creates a demand for big companies to produce cheap durable packaging in high volumes. Think about it. Nearly every item you see in the grocery store comes in some sort of packaging, and before it was put on the shelf it came out of a box, and that box was on a crate which was wrapped in layers of plastic film.

So, what happens to all this packaging?

For the most part it is disposable, which creates an issue when it makes its way into the environment and is unable to break down naturally. To prevent household rubbish from entering the environment we have kerbside waste collection that transports general waste into landfill and recyclable goods to recycling facilities. However once in landfill it takes centuries for these materials to break down, it is therefore preferable to recycle as much as possible.

So, what can you do?

As a consumer our habits determine the habits of big companies. By buying plastic-free goods we can show the big companies that there is a demand for more sustainable packaging. In fact, as recycling became more popular major companies began to use materials that are easier to recycle, leading to the introduction of HDSPE and PETE plastics in the 1980s.

Recycling not only minimises what goes into landfill but also allows us to reuse resources again and again, thereby reducing the need to extract new resources which is expensive both economically and for the environment in terms of the huge greenhouse gas emissions associated with production. In recognition of this, government programs and environmental activists have sought to educate people on recycling.

The government continues to offer incentives for citizens to recycle with the goal that all packaging will be 100% recyclable or compostable by 2025.

Under South Australian state legislation bottles, cans and cartons marked with “10c refund” are able to be taken to participating recycling depots to collect 10 cents per eligible item. In addition to this people must pay a fee for disposal of waste into landfill.

It is estimated that between 2017 and 2018 Australia used 3.4 million tonnes of plastic, of which only 9.4% was recycled. Overall, in Australia we recycle approximately 55% of all waste produced from households and industries. Studies also found that approximately 84% of kerbside recycling was recycled whilst the remainder that went into landfill was primarily a result of things going in the wrong bin.

These statistics demonstrate the need for better education on recycling in households and businesses, as well as better access to the recycling of plastics including soft plastics.

The following can be read as a guide to responsible recycling, it also explains the recycling process and some of the uses for recycled goods. Keep reading to find out how you can become a pro recycler and a more ecofriendly citizen…

Aluminium cans and other metals

Aluminium is the second most used metal in the world, there are therefore many benefits to recycling aluminium products from your home. Aluminium can make its way into your house in the form of canned goods, foil wrap, trays and tin cans amongst other things. In south Australia tin cans can be recycled through the 10c recycling scheme meaning you have the chance to get some of your money back. Other aluminium waste can be disposed through kerbside recycling.

It is important to note that small pieces of aluminium such as the lids from glass bottles and jars make me too small to be placed straight into the bins, instead you can place them together in a larger tin and seal is so they may be recycled properly, coffee or milo tins are great for this!

Once collected and sorted aluminium is crushed and melted at a temperature over 700°C then recast into aluminium ingots. These ingots can then be repurposed into a wide range of uses. The malleability of the material makes it valuable in the construction of buildings, engines and aircrafts. Recycling aluminium is said to save 95% of the energy it takes to create new material from bauxite ore.

Other metals can be recycled through recycling depots, many of which will pay in return for scrap metals. The highest paying scrap metal is copper which can fetch around $9 per kg then next is brass, which will fetch around $6.40 per kg. Steel items will also earn you some cash back at varying rates depending on the grade of steel. Other items scrapped for cash include car batteries, electric motors, and white goods including refrigerators, washing machines, dishwashers and stoves.

The recycling process is similar to that of aluminium where the item will be disassembled with the metal stripped and separate then remelted and cast into ingots that can be reused for the production of new goods.

Glass bottles and jars

Firstly, in South Australia many glass bottles qualify for the deposit refund scheme, so its worth checking the label to see whether you can get some money back. However, wine and spirit bottles as well as glass jar which don’t qualify for a refund can still be recycled in your yellow lid bin. It is important to ensure the material is clean so that it is able to be recycled as even as little as 25 grams of impurities per tonne of glass can result in it being rejected.

The diagram below outlines the process following the collection of glass recyclables. Glass can be recycled over and over again and it is estimated that recycling glass bottles saves 74% of the energy required to make glass bottles from raw materials.

It is important to note that broken glass cannot be accepted for recycling and neither can glass light bulbs as they contain mercury. Light bulbs can instead be deposited at electronic waste outlets.

E-waste

The advancement of technology through recent decades means people are constantly upgrading to the latest model, and as a result, technology and electrical equipment is becoming more disposable. Unfortunately, as a nation we are lagging behind in terms of e-waste recycling.

Studies found Australia to be one of the top e-waste producing countries in 2019. Furthermore, it has been projected that by 2030 Australia will be generating 461 kilotons of e-waste annually. The majority of this waste comes from people’s homes, making it all the more important that we as consumers make the decision to dispose of e-waste responsibly.

Electronic waste is difficult to manage as it contains a diverse range of elements, however this makes it all the more important as many of these metals can have toxic effects if released into the environment, and cause soil and water pollution when put into landfill.

In addition to reducing environmental pollution, recycling of goods allows us to reclaim precious resources, as up to 95% of electronic waste is reusable.

Examples of electronic waste include televisions, computers, phones, speakers, game consoles, cameras, air conditioners, printers, vacuum cleaners, and electric tools.

There are a number of drop off point in south Australia that accept electronic waste, some of which are Unplug N’ Drop, Electronic Recycling Australia, ECycle SA, Edinburgh North Resource Recovery Centre, and Pooraka Resource Recovery Centre.

Plastics

The first synthetic plastic known as bakelite was introduced in 1907, and since then plastic production has increased at an exponential rate. While low-cost manufacturing and durability increased the popularity of plastic, plastic products became disposable, and once disposed of, non-biodegradable. Unfortunately, the majority of plastic waste ends up in landfill, or worse yet, finds its way into waterways which carry it out into the ocean.

To be a more responsible consumer we can start by shopping plastic free, however if plastics are unavoidable the next step is to check the label.

The Australasian Recycling Label is an Australian government endorsed label that tells consumers which parts of a products packaging can be recycled and which parts need to go to landfill.

The majority of hard plastics are able to go into the yellow bin, the chart below shows just some of the types of plastics that can be recycled.

At the recycling centre plastic are sorted into their respective grades (shown in the chart above). They are then compressed into blocks, crushed into pellets, washed then melted down to produce raw materials ready to be processed into new products.

Soft plastics on the other hand can only be recycled through specialised soft plastic recycling services, collection points can be located at major supermarkets. You can identify soft plastics as those which can be scrunched into a ball or broken by hand.

The video below shows how soft plastics are given a second life.

Paper and Cardboard

The other major waste products you’ll find going into your bin are those made of cardboard and paper.

Paper and cardboard are made from tree fibres, the recycling of such items means less trees need to be chopped down to manufacture new products. Recycling is very simple using the yellow lid bin, the main thing is to ensure that the material is clean and dry. Cardboard is produced from recycled paper and can be recycled again and again giving it many lives and uses. Other items that can be made from recycled paper include office paper, tissues, toilet paper, newspapers, magazines, packaging, kitty litter, plasterboard and insulation. During the recycling process the paper pulp is sterilised which means it is also safe for food items such as coffee filters, egg/fruit cartons and paper plates, bowls and cups

Alternatively, there are many great options to recycle paper and cardboard products within your own home. This is even better as it helps save costs of transporting and processing paper waste. Some people find us for recycled paper in creating art, whether it be collages, beads jewellery, paper mâché or handmade paper. If you’re an avid green thumb you may find that you can recycle paper waste into your garden as food for compost or worm farms, mulch, weed blocking, or plant labels.

Green Waste

This brings us to our next topic: green waste. Green waste can be recycled via kerbside collection in the green lidded bin. This may include all organic waste from garden waste to food scraps, you can identify what goes into the green bin by asking the question “was this once a living thing?”

Examples of green waste include lawn clippings, plant prunings, leaves, weeds, pet waste, certified compostable food packaging, egg cartons and greasy cardboard (ie. Pizza boxes), paper towel, tissues and shredded paper

Like with the paper waste, you may choose to recycle your green waste at home in the garden by adding it to a compost heaps or worm farm in order to turn it into a nutrient rich fertiliser than can be used to enhance your garden soil. Things like leaf debris and lawn clippings can be used directly as mulch.

To Recap…

Hopefully you have found this guide useful and it has enlightened you on how you can reduce your impact on the environment as a consumer. To become a more ecofriendly citizen you can remember the three ‘R’s in your day to day life, “Reduce”, “Reuse” and “Recycle”. Firstly, you can start by reducing the amount of waste you produce and resources you use by shopping plastic free and adopting a minimalistic lifestyle by not buying more than you need. Secondly, you can reuse items where you can within your own home whether it be holding onto those plastic containers and bottles, recycling paper for art projects or returning organic waste into fertiliser. Lastly, when it is necessary to dispose of waste you can ensure you do so responsibly by using the guide above to minimise what you put into landfill.

Article by Mary Gordon

This is the story of how the ignorance and needs of mankind drove an essential ecosystem engineer of the Great Southern Reef to near extinction, and how generations of people forgot they even existed in the first place. How can this be? And what are we doing to fix it?

History of oysters on the Great Southern Reef

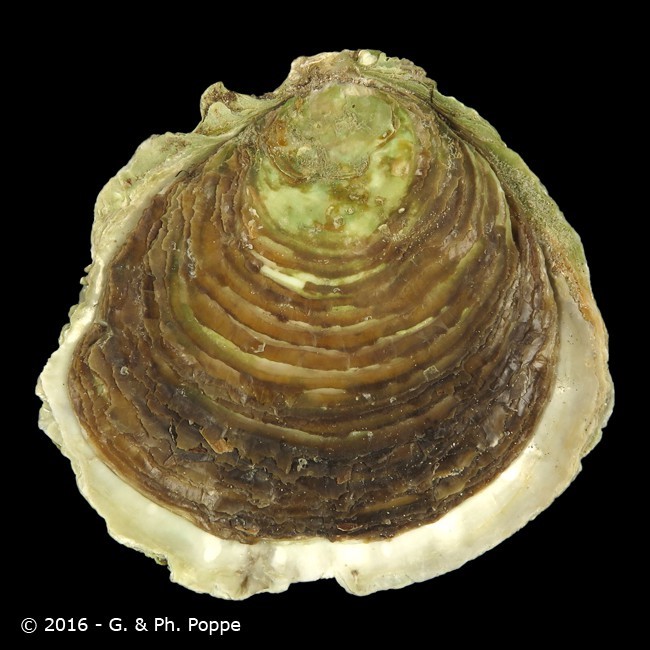

In the 1800s Australian flat oysters or Ostrea angasi (pictured above) were spread across 1500 kilometres of Australia’s southern coast and found commonly throughout South Australia’s gulf and bays. However, dredging, pollution and overfishing caused the species to become extinct.

The following timeline lays out the history of oyster fishing in South Australia and the loss of native oysters as a result of overfishing, water pollution and habitat loss.

A study by Alleway and Connell (2015) investigated historical police records to estimate the quantity of angasi oysters caught by commercial fishers from 1836 to 1944 finding a significantly reduced catch rate from 1886 until 1946 when they were mostly eradicated.

Interestingly, until recently there was no contemporary knowledge of their ecological importance and economic value. Alleway and Connell (2015) go on to discuss the concept of a shifted baseline.

Shifting baseline syndrome is where knowledge of the natural environment is lost over time because people do not perceive the changes taking place, and as the next generation is born, they will accept the state of the environment they are born into, resulting in an “intergenerational amnesia”. Alleway & Connell argue this phenomena “not only undermines progress towards their recovery, but also reduces our expectations of these coastal ecosystems.” This provides a challenge for restoration.

After this discovery people began to realise the potential benefits of native oyster reef reintroduction both to the environment and the economy.

The reintroduction of native oysters back to South Australia’s coast

In 2017 construction on Windara reef began as part of a $3.25 million project announced by the South Australian Government in order to boost the tourism economy, improve water quality, prevent coastal erosion and restore habitats crucial to supporting the fishing industry.

The project involved laying out 150 limestone blocks on the sandy seafloor.

Windara reef is located south of Ardrossan, on the Yorke Peninsula. Initially 4 hectares, it was expanded to 20 hectares in 2018, and in 2019, 50 000 Australian flat oysters were reintroduced to the restored reef. Now over seven million juvenile Australian Flat Oysters have been added to the reef.

Watch the video below to find out more.

Benefits of reintroduction

Firstly, Australian native oysters are an ecologically important species and it would therefore be beneficial for conservation efforts to prioritise the restoration of shellfish reefs.

Oysters have been identified as both a keystone species and an indicator species.

World Wildlife fund website describes a keystone species as “a species that plays an essential role in the structure, functioning or productivity of a habitat or ecosystem at a defined level… Disappearance of such species may lead to significant ecosystem change or dysfunction which may have knock on effects on a broader scale.”

The WWF definition of indicator species is “a species or group of species chosen as an indicator of, or proxy for, the state of an ecosystem or of a certain process within that ecosystem.”

Oysters are benthic filter feeders, meaning they get their food by feeding on suspended particles in the water. As a result of this, “Organisms living on sediments are able to bioaccumulate contaminants”

Bioaccumulation describes “the accumulation of contaminants in the tissues of organisms through any route”.

As a result, Native Oysters could be studied in order to detect and monitor the presence of contaminants in ocean sediments. Hence their reintroduction to South Australia’s coastline could inform responsible wastewater management.

Oysters are considered ecosystem engineers their shells provide the structural diversity in their environment and habitat for other species. The reefs they form act as a natural barrier against coastal erosion by reducing the erosivity of waves and stabilising sediments.

Furthermore, their role as filter feeders benefits other marine life as they are able to reduce turbidity and enrich sediments

Photograph (above) shows Australian flat oyster aquariums at the Marine Discovery Centre, Henley Beach. This display is used to demonstrate oysters’ ability to reduce turbidity.

McAfee, Larkin & Connel summarise that “the utility of bivalve–plant interactions in restoration research is predominantly positive across habitats and species “

Oyster reef reintroductions should be a high priority due to the environmental, social and economic benefits they provide. They have significant ecological value as keystone species, ecosystem engineers and indicator species which can serve the wider marine community and provide ecosystem services for people.

Ecosystem services provided by native oyster reefs include provisioning, regulating and cultural.

Native oysters support the fishing industry through serving marine habitats and enhancing fish recruitment. Through habitat provision, native oyster reefs promote the growth of sought-after species like Snapper and King George Whiting. This creates opportunities for both recreational and commercial fishers.

Furthermore, there is economic value in the farming of native oysters themselves. After the native oysters were fished to extinction, the market turned to the farming of pacific oysters. However, with the first recorded case of POMS (Pacific Oyster Mortality Syndrome) in Australia in 2018 the oyster industry took a hit and farmers have discussed the benefits of ‘diversifying’ by including angasi oysters into their farms.

This audio clip features an interview with Steve Leslie and Yvonne Young from the Oyster Province, an oyster farm that produces Australian flat oysters.

Through their ability to promote the health of marine ecosystems, oyster reef restoration also generates opportunities for nature-based activities for the locals and tourists to enjoy such as snorkelling, diving, fishing, dolphin/seal/ whale watching.

What can we do?

Would you like to try eating a native oyster one day? or continue to enjoy our states beautiful marine life on the Great Southern Reef? the best way you can help is by being educated. These crucial habitats were lost and forgotten in the past because the public were oblivious of their existence and importance. You can also help by getting involved with citizen science organisations such as the Estuary Care Foundation by offering your time as a volunteer (see photo below), or donating money through their website. Additionally, you can donate to the Nature Conservancy Australia’s shellfish reef restoration project

Plastic pollution is globally recognised as an environmental issue with decades of poor waste management leading to the mass amounts of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans.⁴ In 2010, it was estimated that eight million tons of plastic entered the ocean, a statistic that has now almost doubled, with microplastics making up a large proportion of this pollution.⁵ Microplastics are one of the largest rising pollutants of the 21st century as due to their increasing presence in water bodies such as, lakes oceans and seas is growing leading to health risks of marine environments and aquatic organisms.³

What are Microplastics?

Microplastics are minuscule pieces of plastics which range in size from microscopic to 5mm and can be grouped into three different categories: primary, secondary and microfibres. Primary microplastics, also called nurdles, are manufactured products such as microbeads in toothpastes, skin care scrubs and washing powders.¹ Secondary microplastics are particles that have broken down from larger plastic products such as straws, plastic bags and bottles, through degradation from exposure to UV oxidisation, and fragmentation from rapid water movements and abrasions along substrates.⁵ These secondary microplastics continue to breakdown until they are invisible to the naked eye, yet remain in the environment. Microfibres, which are also invisible plastic particles are synthetic fibres which are shed from synthetic fabrics such as polyester from shirts. ¹

How are Microplastics Entering Oceans?

Research suggests that 80% of all plastic pollution in marine ecosystems begins in terrestrial environments with 1.5 million tons of primary microplastics entering the marine environment globally each year.⁵ In South Australia, microplastics are transported into ocean environments via rivers and freshwater catchments, stormwater runoffs, atmospheric transport, and discharge from wastewaters.⁴ With freshwater streams being one of the main contributors of microplastic pollution entering oceans.⁵ Microplastic pollution is correlated with human population and anthropogenic activities and is expected to increase in highly populated cities. An example of how anthropogenic activities increase the amount of microplastics entering oceans is through greywater from household washing machines which can release up to 1,900 microfibres from a single garment during a single wash cycle. Another example of microplastics entering ocean environments is through sand recycling. When sand is transferred, embedded microplastics from one location are transported to another and due to being upturned can re-enter the coastal waters. ⁴

What is the Harm of Microplastics?

There is an estimate of 5 trillion microplastic particles in the ocean worldwide ranging from sediments in the ocean seafloor to the open waters off the coast of the Great Australian Bight.⁴ As microplastic pollution is associated with the human population, high concentrations of microplastics are generally found near urbanised areas due to the plastics entering oceans from rivers and other land-based sources, yet remote locations can also have high microplastic concentrations.⁵ While the South Australian coastline has a low population density compared to other global coasts the concentrations of microplastics are low to moderate.⁴ The South Australian coast is a global biodiversity hotspot with many endemic species and contains an environment that is sensitive to changes. Coffin Bay supports an ecosystem that is more diverse than the great barrier reef and Point Lowly in Whyalla is the only known breeding ground of the Northern Spencer Gulf subspecies of Giant Cuttlefish (Sepia apama). ⁴ These diverse and endemic ecosystems are likely to see detrimental effects from increasing microplastic concentrations as microplastics directly affect marine life as well as marine environments shown in figures 1 and 2 below. ³

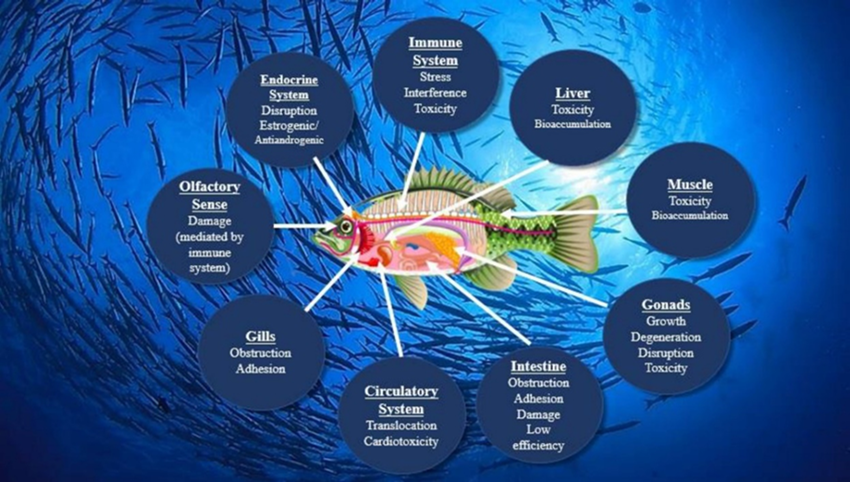

Figure 1: The impacts of microplastics on aquatic organisms once ingested. (Image taken from Gola et al. 2021).

Figure 2: The pathway of plastics and microplastics entering oceans and the adverse effects on aquatic life and how it impacts humans. (Image taken from Gola et al. 2023).

Microplastics are ingested by fish, including zooplankton, the smallest animal, due to the small size of the plastics being hard to see in ocean water. Once ingested, microplastics result in many health problems such as liver damage, blockage of body tracts and reduced fertility. ³ Along with harming fish and small aquatic organisms, microplastics are also ingested by larger aquatic organisms and even humans when we consume contaminated seafood. ²

Are there any Solutions?

Fighting against a microscopic plastic that has already entered the ocean seems impossible, however correct plastic waste management can help with microplastic reduction. Banning single use plastic products and products that contain microplastics such as beauty products with microbeads will also help reduce the amount of plastics produced.¹ Stricter policies on plastic use that apply to large industries and the public can help to implement less plastic ending up as waste which will hopefully result in a healthier ocean environment and improve human health.³

References

1 Australian Marine Conservation Society 2023, Microplastics, Australian Marine Conservation Society, viewed 10 May 2023 https://www.marineconservation.org.au/microplastics/.

2 Cox, KD, Covernton, GA, Davies, HL, Dower, JF, Juanes, F & Dudas, SE 2019, ‘Human Consumption of Microplastics’, Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 53, no. 12, pp. 7068–7074.

3 Gola, D, Tyagi, PK, Arya, A, Chauan, N, Agarwal, M, Sing, SK & Gola, S 2021, ‘The impact of microplastics on marine environment: A review’, Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management, vol. 16, no. 100552.

4 Klein, JR, Beaman, J, Kirkbride, KP, Patten, C & Burke da Silva, K 2022, ‘Microplastics in intertidal water of South Australia and the mussel Mytilus spp.; the contrasting effect of population on concentration’, The Science of the Total Environment, vol. 831, pp. 154875–154875.

5 Leterme, SC, Tuuri, EM, Drummond, WJ, Jones, R & Gascooke, JR 2023, ‘Microplastics in urban freshwater streams in Adelaide, Australia: A source of plastic pollution in the Gulf St Vincent’, The Science of the Total Environment, vol. 856, pp. 158672–158672.

The chemistry behind ocean acidification

Written by: Alya Arief Azali

Excessive carbon dioxide emissions are a key driver in global warming, but did you know carbon dioxide also increases ocean acidity?

Ocean acidification is the rise of ocean acidity due to the absorption of excess carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. The ocean holds many finely balanced chemical reactions. However, anthropogenic sources of CO2 puts these reactions out of balance, resulting in adverse effects, such as ocean acidification.

We can use chemistry to explain the process of increased ocean acidity. Specific chemical reactions can shift forward or backwards, like the reactions used to describe ocean acidification. These reactions are called equilibriums and proceed forward or backward depending on the system's concentration, pressure and temperature. When these factors in an equilibrium are out of balance, the reaction will change its direction to maintain balance. You can liken this balance to that of a weighted scale.

In the case of ocean acidification, we start with a balanced system, like so:

The carbon dioxide produced by humans increases the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the water, putting the scale off balance, like so:

So, the amount of hydrogen ions (H+) in the system increases to bring the system back to equilibrium.

This increase in hydrogen ions increases the acidity of the water.

Many marine animals combine calcium and carbonate, building their shells and skeletons from the mineral calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Calcium carbonate also exists in equilibrium in water. As the acidity of the water increases, hydrogen ions react with carbonate to form bicarbonate. The formation of bicarbonate reduces the amount of carbonate available for marine life to form their shells and skeletons. Increased acidity can dissolve calcium carbonate structures because the equilibrium shifts to the right to compensate for the lost carbonate. In fact, in cases of very high acidity, these structures may be dissolving faster than it takes calcifying creatures, such as crabs, sea urchins and coral, to build them.

Suppose these creatures lose the ability to form integral structures. In that case, it can lead to the eventual extinction of the animal and its many associated species. Moreover, species extinction can throw ecological systems out of balance, resulting in substantial trickle-down effects on human food security and livelihood.

The only long-term solution to ocean acidification is decreasing carbon dioxide emissions. Governments have set international targets to keep global warming under check. However, these targets focus on lowering non-CO2 greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide, which have a higher global warming potential and are less costly to reduce. Ocean acidification, driven by excess CO2 emissions, has no set target. Instead, this area is left for individual countries to decide on.

The natural world relies heavily upon balance. It is time humans consider their actions and impacts as part of this balance, and governments make policies that support the complex life systems around us.

References

Doney, SC, Busch, DS, Cooley, SR & Kroeker, KJ 2020, 'The Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Marine Ecosystems and Reliant Human Communities', Annual Review of Environment and Resources, vol. 45, no. 1, 2020/10/17, pp. 83-112.

Dupont, S 2013, Ocean acidification is chemistry, not conjecture, viewed 19/03/23, <https://theconversation.com/ocean-acidification-is-chemistry-not-conjecture-15497>.

EPA 2022, Effects of Ocean and Coastal Acidification on Marine Life, viewed 19/03/23, <https://www.epa.gov/ocean-acidification/effects-ocean-and-coastal-acidification-marine-life#:~:text=Many%20ocean%20plants%20and%20animals,calcium%20carbonate%20calcium%20carbonate%203.>.

Harrould-Kolieb, E 2015, Ocean acidification: the forgotten piece of the carbon puzzle, viewed 19/03/23, <https://theconversation.com/ocean-acidification-the-forgotten-piece-of-the-carbon-puzzle-50247>.

Scott, K 2021, COP26 failed to address ocean acidification, but the law of the seas means states must protect the world’s oceans, viewed 19/03/23, < https://theconversation.com/cop26-failed-to-address-ocean-acidification-but-the-law-of-the-seas-means-states-must-protect-the-worlds-oceans-171949>.

On Thursday 23 February 2023 the MDC welcomed invited guests to the ‘Reimagining the Marine Discovery Centre’ event. In 41 degree heat we thank the 100 guests who came to see the upgraded centre.

Matt Cowdrey MP – member for Colton was our distinguished guest wearing many hats including representing the Minister for Education, Blair Boyer. Councillor Kenzie van den Nieuwelaar represented the City of Charles Sturt.

Professor Chris Daniels, MDC’s esteemed Patron, emceed the event introducing Dr Zoe Doubleday as our special guest speaker, sharing her knowledge and expertise, Heaps Good Productions, Michael Mills provided the wonderful pre speech entertainment. Karno Martin welcomed our guests to Countr,y and Carmen Bishop shared with guests the journey of the MDC of the last 25 years from being the brainchild of the original Director, Tim Hoile to what the future holds and how our dedicated team of staff and volunteers will continue to educate 7,000+ students every year about South Australia’s marine environment and MDC's continued reimagined growth.

Thank you to Green Adelaide for supporting this event their continued support of marine education in South Australia

Thank you Patritti Wines and Adelaide Classic Catering for the quality refreshments and catering

The centre wouldn’t be what it is with thanks to our dedicated team of volunteers who have donated 2,280 hours of their time in the last 2 years. This equates to almost $100,000 of labour.

Thank you for attending and your continued support AAEE SA Chapter, Butterfly Conservation SA, Catholic Education SA, Cleland Wildlife Park, Community Bank West Beach, Conservation Council SA, Conservation Volunteers Australia, Department for Environment and Water, Department for Education SA, Department for Primary Industries and Regions PIRSA, Experiencing Marine Sanctuaries, Fastbreak Films, Friends of Gulf St Vincent, GHD, Visit Henley Beach, Inspiring South Australia, jimloste, Junior Field Naturalists, KESAB, Marine Impressions, Great Southern Reef, Marine Life Society of SA, MOD. UniSA, Monkeystack, National Science Week SA, Nueplex, Ocean Imaging, Outdoors Indoors, Port Environment Centre, Positure, AUSMAP, SA Museum, SA Science Teachers Association, Science Alive!, Seastar Rock Productions, Star of the Sea School, TAFE SA, Tennyson Dunes Group, The Science Collective, University of Adelaide, UniSA, WACRA, and all of our other supporters.

Carmen Bishop speech

Good afternoon everyone,

Welcome to the Marine Discovery Centre and thank you for taking the time to come and visit us this afternoon, especially on this 41 degree day.

I would firstly like to thank Green Adelaide for their continued support, and their assistance with putting this event on. Also to the many other supporters who align with our mission and are here with us today. Without your continued support, the Marine Discovery Centre wouldn’t be the institution in South Australia that it is today.

I would like to make special mention of our patrons Chris Daniels (who has kindly invited you here and is emceeing todays proceedings) and Karl Telfer (who is unable to be with us today, but we are lucky to have Karno, his nephew as a key part of the team at the MDC and is vital in sharing Aboriginal Culture and knowledge to every visitor here). I would also like to acknowledge the first patrons of the MDC, Barbara Hardy and Andrew McLeod. The original visionaries.

From humble beginnings, the story of the MDC.

The Centre was the brainchild of then Star of the Sea - Marine Studies Coordinator, Tim Hoile. Tim had a vision. His love of the marine environment started with two seahorses in an aquarium outside of his classroom. This grew to a few more aquariums and with the support of then Principal Sister Enid when this property came up for sale she purchased with the support of the Henley Beach Parish.

Tim is unable to be here today but those of you that know him, you’ll be happy to know he is enjoying himself overseas with his love of surfing. But I would like to personally welcome Peter Hoskin who is here today and was central to setting up the centre from that very first day with Tim.

The Marine Discovery Centre was officially opened on October 31 1997, with the project being made possible through funding from Coastcare, Fisheries Action Program, Landcare, KESAB and the Marine and Coastal Schools Program.

On Friday 26 March 2010 Senator Penny Wong, Federal Minister for Climate Change and Water, officially opened a newly refurbished MDC.

In 2018, the centre completed another major redevelopment following the Fund My Neighbourhood grant win of $170,000.

In 2020, the centre was able to upgrade its educational interactive resources thanks to a $95,000 grant from Green Adelaide. And now in 2023, we welcome you to be part of reimagining the Marine Discovery Centre.

As a vital educational facility, one of the main goals of the centre is to raise awareness about the importance of marine conservation. The centre provides visitors with an opportunity to learn about the diverse marine life that can be found in the waters of South Australia and the Great Southern Reef. They not only learn that 90% of our species are endemic to these waters, they also learn about the impacts of human activities on marine life, such as pollution and overfishing, and how we can all take steps to protect our oceans. Our programs also focus on ecological sustainability and Kaurna culture its connection to land and sea country.

The Centre offers a variety of marine conservation and Aboriginal educational programs for schools and community groups, including excursions and incursions.

More than 7,000 students take part of this program every year and become immersed in discoveries about our local environment.

Improving the quality of learning experiences is vital in an ongoing vision to empower students and the community through inspirational and interactive discovery.

Georgie Kenning our resident marine scientist has been instrumental in not only looking after our marine life but educating the student visitors to the MDC. Her delivery is inspiring the minds of the future environmental leaders of South Australia.

Karno Martin is the MDC’s Cultural Educator who leads the cultural education program to the thousands of visitors every year. He runs his program not only from the Meyunna Wodli inside the centre but also outside on Country, introducing students and community members to the medicinal uses of plants and the sustainable living practices our First Nations people lived by. Learnings that are not taught in the every day classroom, but what every person living on Kaurna land should be inspired to know.

While the Marine Discovery Centre is a valuable resource for the community, it would not be possible without the support of our dedicated volunteers. Volunteers, university interns and work experience students have volunteered 2,280 hours of their time in the last 2 years alone which equals almost $100,000 of labour. This is mutually beneficial program as they are able to secure employment in their fields based on quality work experience they have undertaken here.

This centre wouldn’t be what it is today without the continued support of people who want to educate the South Australian community and we thank our donors, supporters and partners. Their time, money, and effort help the centre to continue its mission of educating the public and protecting marine life.

So why are we here today.

We want to inspire you, showcase the centre and take you on the journey with us for how we can reimagine and grow the MDC for the next 25 years.

I can say the word Nemo, and you all know who I mean. Why can’t we do the same to our Porcupinefish, the Port Jackson Shark, the Southern Fidler Ray, the Leafy Sea Dragon and many more of our other local treasures. Did you know that the majority of Australians think the Great Barrier Reef has more species than the Great Southern Reef, you know their wrong, we are to here educate.

As a child who was educated in South Australia, I knew more about the Great Barrier Reef and Pacific Ocean than I did about our local coast. It seems many visitors are the same. Personally, for the 3 years I have been here I have learnt more about our marine environment than I did than my 40 plus years combined before. Children and adults alike leave here in awe and a with new-found appreciation for our marine environment and the first steps of taking ownership to protect it.

We’ve had children here that have never seen the ocean, or stepped on sand, children that had no idea the amazing marine life that exist in their own backyard. Children who have taken key facts back home to their families about even the basics of using the right bin for their rubbish, recycling or compost waste. Think of the dinner table discussions we are creating.

We are accessible to all schools, all students. We’re not only educating and showing them our local marine life, we are empowering them to protect it.

But we do have challenges.

Sometimes we feel like we are a victim of our own success.

Challenges include our high visitation but minimal space, we can only fit a certain number of students in at any one time. We also have to turn bookings away during our peak season.

With 3 paid staff and a reliance on volunteers we can only open to the public once a month. Every single Open Day sells out, there is a strong demand for this service.

We currently educate 7000 students, we could easily welcome 30,000 plus annually if we had the capacity to open our doors more.

In today’s economy we can’t increase the cost of excursions. A lot of schools can’t pass on these costs on to families, plus the increasing costs of bus hire. Perhaps we need our own bus?

Excursions only cover 20% of our operating costs. But like I said we can’t increase these costs. The people that need to know the steps to actively protect our environment can’t afford it.

We are making a difference. We are all here today with the same love for our environment and also the knowledge of why it’s so important to empower our next generation to not only follow suit but make it better.

We need to grow

We have high visitation. Already this year we have increased excursions by 400% for the January – April period versus the same period for last year

We not only survived Covid, we thrived, the moment we were closed, not by choice, we changed our game plan. We went online, we created online apps, videos, easily accessible curriculum plans. We got people to enjoy and learn about the local SA environment in their own time. We were also able to reach people in regional areas. We saw not only the need but also the want for more information about the South Australian Coastline. We found new resources to create.

We are not only key for education and marine and environmental conservation, we can be a pivotal part of South Australian tourism. We together can share South Australia’s best kept secret. We can continue the discussion with smart partnerships.

I look forward to welcoming you inside, our dedicated team of staff and volunteers are there to answer all of your questions.

We are also excited to announce our new children’s program: Porcis Ocean Patrol a series we are creating with Fastbreak Films. Kylie Claude the producer of Fastbreak Films has kindly donated her time and will be in the Discovery Room sharing the vision we have of educating the world on the big screen

Georgie, Karno and I will be following up over the next week with phone calls and a survey to get your input and your thoughts of the centre and its next steps. We want your opinion for a shared vision on empowering and educating our future about South Australia’s marine environment.

Together we can make a difference.

Thank you.

You may like to pair oysters with a nice glass of champagne or with lemon and tabasco, but have you ever thought about their mysterious lives beneath the sea? There is a reason South Australia is famous for their oysters and not just the ones that end up on your plate at a fine dining restaurant. Oysters are in fact ecological superheroes and form a vital part of our Great Southern Reef here in southern Australia.

The last surviving native mud oyster reef in Georges Bay, Tasmania. Credit: Chris Gillies.

Like the rainforests are the lungs of the planet, oysters are the kidneys of our oceans. A single oyster can filter up to 100 litres of water a day. Transfer that to the millions of oysters on a reef and the filtering capacity is incredible! With clearer waters allowing more sunlight as well as a nutrient rich sea floor, thanks to the deposition of oyster faeces, neighbouring seagrass meadows flourish. This in turn, encourages more species to establish in these habitats and ultimately, underpins the coastal food web. The deposition of oyster faeces also promotes the growth of specific bacteria which convert excess nitrogen into nitrogen gas. This helps to prevent algal blooms which can be detrimental to the growth of other species.

What’s more, aggregations of oysters provide a haven for a diversity of small fish and invertebrates. Just a 25cm squared patch of oysters can host more than 1000 individual invertebrates! Not only do these habitats bolster an array of marine life, but oyster shells also cast shade, trap moisture, and provide shelter for semi-aquatic animals like snails and crabs. These animals live on intertidal rocky shores and are particularly susceptible to extreme temperature changes during low tide. The aggregated shells of oysters help counteract these climatic extremes with temperatures up to 10°C cooler than neighbouring habitats during hot days.

The physical structure of oysters also dissipates wave energy which helps to protect saltmarshes and corresponding coastlines from erosion. If that’s not enough, oysters are essentially carbon sinks as well! Their shells made from calcium carbonate are buried and compacted to rock, which helps to prevent carbon dioxide from cycling back into the atmosphere.

If you have ever heard the saying, “the world is your oyster”, well, that is certainly the truth for these temperate marine ecosystems. Unfortunately, though, over 90% of Australia’s oyster reefs have vanished since European settlement. Once forming extensive reefs along more than 1500km of South Australia’s own coastline, the native mud oyster, Ostrea angasi, remains as only one healthy reef in Tasmania.

A healthy oyster reef in Tasmania as South Australian reefs would have been in 1836 (left) compared to the remnant seafloor today (right). Credit: Chris Gilles.

Archaeological research shows that for over 5000 years, the Indigenous people of Australia sustainably harvested oysters and replenished the populations by building reefs from stones and shells. But after colonisation, Europeans harvested oysters for food and burnt their shells to create lime for cement and fertilisers. Although these extensive fishery efforts ended over a century ago, the once abundant oyster populations were never able to recover. Baby oysters rely on the shells of their ancestors as a substrate to settle on and grow, but subsequent dredging of the sea floor and additional sedimentation removed any chances for them to regrow.

However, all was not lost for our ecological superhero oysters. Recent reef restoration projects show a promising future for these precious marine ecosystems. There are currently 46 shellfish reef restorations underway in Australia. One of our very own projects in South Australia, the 20-hectare Windara Reef, is the largest of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere. These man-made reefs, which use limestone or old shells to provide substrate for oysters, have been settled by baby oysters within months of construction. The enormous success so far is due to public support, with many coastal communities leading these restoration programs.

Discarded oyster shells from restaurants are being recycled into man-made reef structures as part of a community-led oyster restoration program. Credit: OzFish.

Once at the brink of extinction, oysters are now at the forefront of conservation, and rightfully so. Without these ecological superheroes, we would lose the precious marine life that sustains biodiversity and the livelihoods of many people.

Written by Chelsea Foubister

References

Baczkowski, H 2021, ‘Waste oyster shells getting a second life after being recycled to create artificial reefs’, ABC News, 16 October, viewed 5 October 2022, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-16/oyster-shell-waste-artificial-reef/100538272>.

McAfee, D & Connell, S 2017, ‘Huge restored reef aims to bring South Australia’s oysters back from the brink’, The Conversation, 28 June, viewed 4 September 2022, <https://theconversation.com/huge-restored-reef-aims-to-bring-south-australias-oysters-back-from-the-brink-77405>.

McAfee, D 2018, ‘The surprising benefits of oysters (and no, it’s not what you’re thinking)’, The Conversation, 19 February, viewed 4 September 2022, <https://theconversation.com/the-surprising-benefits-of-oysters-and-no-its-not-what-youre-thinking-90697>.

McAfee, D, Gillies, C, Crawford, C, McLeod, I & Connell, S 2022, ‘Once the fish factories and ‘kidneys’ of colder seas, Australia’s decimated shellfish reefs are coming back’, The Conversation, 9 August, viewed 4 September 2022, <https://theconversation.com/once-the-fish-factories-and-kidneys-of-colder-seas-australias-decimated-shellfish-reefs-are-coming-back-184063>.

Preston, J 2019, ‘The world’s most degraded marine ecosystem could be about to make a comeback’, The Conversation, 3 May, viewed 4 September 2022, <https://theconversation.com/the-worlds-most-degraded-marine-ecosystem-could-be-about-to-make-a-comeback-110233>.

In 2018 tourism on the Fleurieu Peninsula contributed $493 million in visitor expenditure with 771 000 overnight visitors per year, 78 % of which being from South Australia (18% interstate, 4% international). The Fleurieu Peninsula encompasses 4 national parks including Granite Island Recreation Park, Encounter Marine Park, Onkaparinga River national Park/ Recreation Park and Deep Creek Conservation Park. The region is also known for its wine and food industry (Fleurieu Peninsula National parks visitation snapshot 2021). The tourism industry as a whole has been hit hard by the recent Covid19 pandemic. A paper published by Tourism Research Australia outlines the role of domestic travel in Australia’s tourism recovery. (Australian Tourism in 2020 2021).

Tourist are drawn to the Fleurieu coastline for its unique wildlife, the Fleurieu Peninsula webpage highlights wildlife attractions such as whale watching, dolphins & seals, little penguins, leafy sea dragons and birdlife (Fleurieu Peninsula Tourism 2021). It is therefore highly important that tourism growth in the area has a strong focus on protecting iconic species. In order to guide management plans, it is first important to understand the way in which these animals are impacted by tourism on the Fleurieu Peninsula. With growth of tourism comes increased human traffic which can disturb natural animal behaviour and introduce invasive species and biosecurity risks, plastic pollution, land degradation and erosion.

The following article focusses on the effects of tourism on Leafy Sea-dragons at Rapid Bay, Hooded Plovers on the Fleurieu’s sandy beaches and Little Penguins on Granite Island.

"Leafy Sea Dragon (Phycodurus eques)" by jeffk42 is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Leafy Sea-dragons

The Leafy Sea-dragon (Phycodurus eques) is one of two sea-dragon species (members of the pipefish family Sygnathidae) that are found only along Australia’s Southern coast. Its name is drawn from the leaf-like appendages on the animal’s body that enables it to camouflage against its kelp forest habitat, they are also able to change colour to adapt to their surrounding (Parks and Wildlife Service 2015). The Leafy Seadragon is the marine emblem of South Australia and the best place to find them is at Rapid Bay, particularly in the reef surrounding the old jetty.